10 to 25: The Science of Motivating Young People DAVID YEAGER, PHD ·

SIMON & SCHUSTER © 2024 · 464 PAGES

Don’t BuyBook Here.

10-to-25 – pdf to read or listen here –

Jamie’s Super Pared Down Version.

-

- Mentors Dilema – even constructive feedback may be perceived as harsh & may arouse resentment.

- Wise feedback – Prefixed with “I am giving you these comments because I have very high standards, and I know that you can reach them”. Students were TWICE as likely to revise their work.

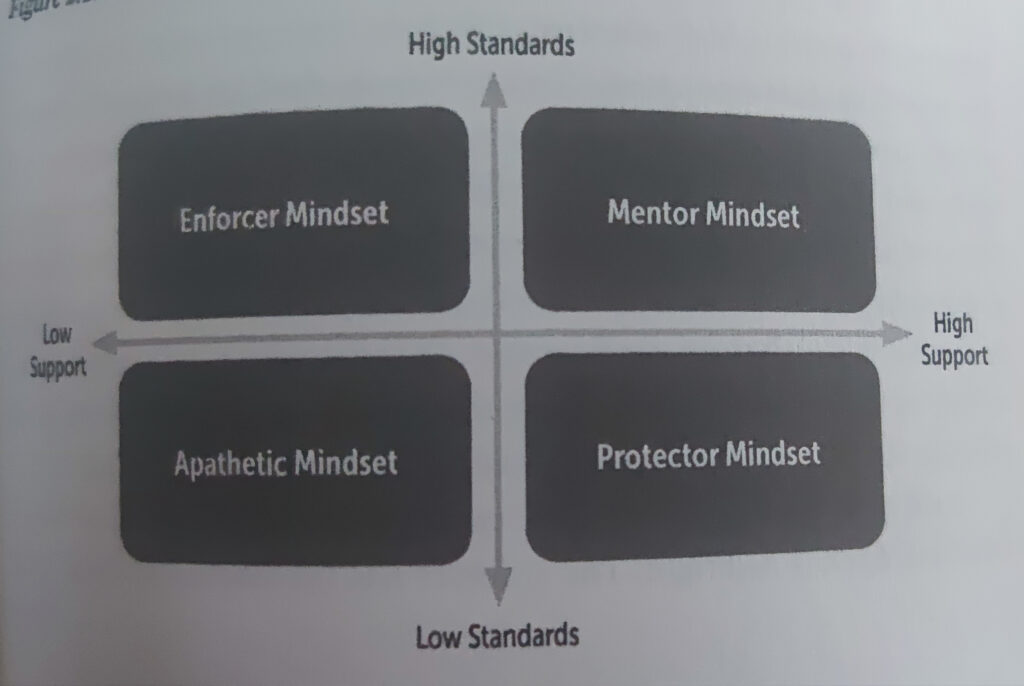

- The Mentor Mindset – High Standards AND High Support – Don’t be a low rigour pushover / protector, or a Dictator / Enforcer.

- Transparency & The Five Practices –

- Make it all bloody obvious (I did not make it unavoidably clear that “I love you & want the best for you, and will help you in any way I can to enable you to fulfil your potential / self actualise.”

- Questioning – Tell less, ask more. “Asking questions—particularly ones that launch us into joint problem-solving, collaborative-troubleshooting mode—can show young people that we need to work together to understand the mismatch of priorities.”

- Stress – Sadly symptoms of stress & excitement are almost the same, increased heart rate, dry mouth, butterflies in tummy, sweaty palms, etc, & so get confused. If you believe “Stress is debilitating” it will be. And then you will get stressed about being stressed. Truth is, stress is not debilitating or negative, it is a by product of us choosing to do something that is hard, but is important enough to us to motivate us to have a go. Instead believe “Stress is just excitement, so it is life enhancing, it means I am outside of my Comfort Zone & I am growing”

- Purpose – Make the connection between what we are doing now & why we are doing it, for their own benefit & for something bigger than themselves. Short term pain, long term gain. Self discipline is 2x a better indicator of success than IQ.

- Belonging. “We secure our sense of belonging through experiences of looking competent in front of the people whose opinions we care about—earned prestige.” “Status and respect are to a young person what food and sleep are to a baby—core needs that, when satisfied, can unlock better motivation and behaviour.” And if you don’t provide them, their peer group will, in much less positive ways.

-

-

Growth-Mindset Messaging: Tell yourself / your mentee – “When you’re faced with difficult challenges and you keep trying until you get better, your brain grows new connections and becomes better at taking on new challenges in the future. … When something does feel really difficult, your brain learns how to respond more effectively to that challenge. It’s a lot like the way rigorous exercise makes your muscles really sore at first but, with training, your muscles don’t just get stronger, they also recover more quickly when you push them to their limit.”

-

Stress-Can-Be-Enhancing Messaging: Tell yourself / your mentee – “People often mistake their body’s stress response for a sign that they’re in a situation they can’t handle. It’s easy to do—racing heart, fast breathing, sweating—these are also ways our bodies respond in emergencies, when we’re in real trouble. This is a mistake that actually can cause you to perform worse because, if you think your stress response is a problem, you’re more likely to be worried about it and get distracted from performing. … You can use your body’s stress response effectively next time you feel it kicking in while you’re trying to perform or master something difficult. When you start to feel anxious, try to remind yourself that this is your body’s way of helping you rise and meet the challenge you’re facing. That should help you to spend less time worrying about the fact that you feel anxious. Then you can focus on what you’re doing and let your body’s stress response give you the extra boost you need.”

- A Micro-Moment Of Life-Changing Encouragement – Awesome ripples in a moment of inspiration, that we are all capable of.

-

Feedback & Improvement welcomed & encouraged by Jamie at immhtr@gmail.com

—————————————-

“It seems like everywhere you turn, you hear older adults—Gen Xers, millennials,

and boomers—describing young people today in dark and despairing terms. In

my eighteen years as a developmental scientist, and thirteen years as a parent,

I’ve heard it in the bleachers at my kids’ games, in the boardrooms of major

corporations I’ve consulted for, and by the watercolors at schools I’ve visited.

They just don’t care. They speak a different language. They’re entitled. They’re too

sensitive. But imagine a world in which older adults interact with young people,

aged ten to twenty-five, in ways that reliably leave the next generation feeling

inspired, enthusiastic, and ready to contribute—rather than disengaged, outraged,

worried, or overwhelmed.

In this world, managers’ work will be easier because their younger employees will

be motivated and self-sufficient. Parents will be happier because they won’t have

to dread their children turning into teenagers. Educators will feel more successful

and less burned-out because they can reach a stressed-out or disengaged

generation of young people. And all the rest of us will be able to bridge the divide

between the generations with confidence without starting a war of words.

I’ve seen this world in the lives of great managers, parents, educators, and coaches.

I’ve studied what they do and how they talk. I’ve used the scientific method—

hypothesis, experiment, data, results—to understand why they’re effective. I wrote

this book because I want to share the secrets I’ve learned. This book is for anyone

who wants to experience this better world firsthand in their interactions with

young people aged ten to twenty-five. It shows how to stop clashing with the next

generation and start inspiring them.”

As per the back flap of the book: “David Yeager, PhD, is a professor of psychology at the

University of Texas at Austin and a cofounder of the Texas Behavioral Science and Policy

Institute. His research has been featured everywhere from The New York Times and The Wall

Street Journal to Scientific American, CNN, Fox News, and The Atlantic.

Yeager is the only developmental scientist to have won all three of the major awards for

early career contributions to developmental psychology, and the only one to have won ‘best

paper’ awards in four different fields: behavioral science, social psychology, developmental

psychology, and education. He got his PhD and MA at Stanford University and his BA and

MEd at the University of Notre Dame.” (Go Fighting Irish!)

In other words, he’s one of THE most respected developmental and social psychologists in the

world. The book is PACKED with Big Ideas and we’re barely going to scratch the surface of its

wisdom. Let’s get straight to work!

THE MENTOR’S DILEMMA & WISE FEEDBACK

“In 2014 I published a scientific experiment with Geoffrey Cohen (and others) on a simple but

effective solution to the mentor’s dilemma. We called it wise feedback. We had instructors be

critical with their feedback but accompany that criticism with a clear and transparent statement

about the reason they were giving that feedback—namely that they believed the student could

meet a high standard if they got the right support. So-called wise feedback is wise (or attuned) to

the predicament of young people who don’t want to be held to an impossible standard and who

also don’t want to be talked down to.

We tested wise feedback in an experiment with middle school students in social studies

classrooms. The seventh-grade students wrote first drafts of five-paragraph essays about their

personal heroes. Next, teachers covered the essays with critical comments and suggestions:

You need to put a comma here. Explain this idea further. Rearrange that sentence. Before

the students got the essays, though, the research team attached handwritten notes from the

teachers—either a treatment note or a control note. (Teachers wrote the notes, but they didn’t

know which student got which note or what the study was trying to test.)

Half the students, randomly assigned, got the treatment note with the wise feedback, which said,

I’m giving you these comments because I have very high standards and I know that you can

reach them. The other half of the students got a vague control-group note. I’m giving you these

comments so that you’ll have feedback on your essay. That note conveyed no clear reason for

the feedback. …

We were hoping that the wise feedback would motivate students in the treatment group to

work harder on their revisions. But even we were surprised by how strongly they responded.

When students received the wise-feedback note, they were twice as likely to revise their essays:

40 percent of the students in the control group revised their essays, but 80 percent did in the

treatment group.”

That’s from page 5 of the Introduction. It captures the thesis and practical wisdom of the book.

Right before that study, David tells us about what he describes as the “mentor’s dilemma.”

He tells us that “it’s very hard to simultaneously criticize someone’s work and motivate them

because criticism can crush a young person’s confidence. It’s a dilemma because leaders feel

like they’re stuck between two bad choices. They could either put up with poor performance

(but be nice) or demand high performance (but be cruel). Neither option is ideal. All too often,

both sides—younger and older—tend to leave these interactions frustrated or offended, even

though both sides might have entered the interaction with growth in mind.”

So… Back to the wise feedback study.

To quickly recap: Randomly assign middle schoolers into two groups. Have them write a first

draft of a five-paragraph essay on one of their favorite heroes. (Awesome.) Then give them

feedback on their essay. HALF of them get a note that says “I’m giving you these comments

because I have very high standards and I know that you can reach them” while the *other* half

gets a note saying “I’m giving you these comments so that you’ll have feedback on your essay.”

What happens? TWICE as many kids in the “wise feedback” group work hard to get better.

As David says: “Here’s the takeaway: When you hold young people to high standards and make

it clear that you believe they can meet these standards, you are respecting them because you

are taking them seriously. Young people rise to meet the challenge because being respected is

motivating. Further, you lift up all students and see greater equity.”

P.S. Another big fan of the book is Angela Duckworth. In Grit, she tells us about “wise

parenting.” Same basic idea. The short story? Wise Parents are BOTH warm AND demanding.

They have high standards AND total support. On the other hand, what Angela calls

Authoritarian Parents have high standards but low warmth. Permissive Parents have high

warmth but low standards. Neglectful have neither.

THE MENTOR MINDSET

“Through years of observing and interviewing these leaders, I discovered what distinguished

them from their less-successful colleagues: their mentor mindsets. This mindset is consistent

with the lesson of the wise-feedback note, of course, but it is also more profound and nuanced.

I called it a mindset because it was a worldview and suite of behaviors. It went beyond simple

statements and included concrete actions. What’s more, these mentor-mindset leaders were far

more effective than peers who used enforcer or protector mindsets.

The simplest way to understand these mindsets—enforcer, protector, and mentor—is to examine

the framework presented in figure 2.1. The first thing to notice is that there isn’t just one axis—

rigor—that organizes leaders’ approaches with young people. It’s not the case that we can only be

low-rigor pushovers (i.e., the protector) or high-rigor dictators (i.e., the enforcer). In fact, there

are two axes. You can have high standards and high support. You can be a mentor.

Think of two perpendicular dimensions. … One is standards (i.e., rigor or expectations) and the

other is support (social, emotional, or material). High standards, low support: that’s the enforcer

mindset. High support, low standards: that’s the protector mindset. High standards, high

support: that’s the mentor mindset. (There’s a fourth quadrant in the bottom left, the apathetic

mindset. These checked-out people tend to end up in either the enforcer or protector quadrants

when they reengage anyway, so there isn’t much use in describing them.)”

After David walks us through “What We Get Wrong” about our relationships with the younger

generation in chapter #1, in chapter #2 he walks us through how to get it right.

While the wise feedback is a great standalone idea, the MENTOR MINDSET is a great lifetime

leadership practice.

To recap… When we have high standards but low support, we are in the enforcer mindset. When

we have low standards and high support, we’re in the protector mindset. When we have BOTH

high standards AND high support, we are in the mentor mindset.

THAT’s where we want to play.

As David tells us: “Enforcers can build on their high standards by adding more support.

Protectors can build on their care and concern by adding higher standards. Both are halfright, and so both just need to add one element to get it all the way right.”

Here are some quick ideas on how to go about doing that…

TRANSPARENCY

“You’ve got a mentor mindset. You maintain high standards. You’re supportive. But do the young

people in your life know it? If they don’t understand how your leadership can help unlock their

potential, then your actions won’t motivate them nearly as much as they could. Transparency

about mentor-mindset actions makes a difference, and anyone can start being transparent right

away. You simply explain what you’re doing and why.”

That’s from the first chapter in Section II which is all about “Mentor-Mindset Practices.” After

we get the Theory on the power of the Mentor Mindset, it’s time to move to Practice. David gives

us FIVE core practices—each of which gets its own chapter:

1. Transparency. You need to EXPLICITLY TELL the kids you parent/young adults you lead

what your intentions are. For example: “I’m REALLY committed to helping you activate

your potential—which I think is extraordinary. To crush it together, I’m going to hold you

to high standards of excellence AND I’m going to help you hit those standards. Let’s go!”

2. Questioning. TELL less and ASK more. David says: “Asking questions—particularly ones

that launch us into joint problem-solving, collaborative-troubleshooting mode—can show

young people that we need to work together to understand the mismatch of priorities.”

3. Stress. We’re going to focus on this in the next Idea. Time to eat stress like an energy bar. 🙂

4. Purpose. David worked with William Damon AND Carol Dweck at Stanford. (Lucky guy!)

Helping the 10- to 25-year-olds we lead MAKE THE CONNECTION between what they’re

doing NOW and WHY they’re doing it (both for their own benefit and for something bigger

than themselves!) is super important.

5. Belonging. David walks us through the new science of belonging. It’s POWERFUL. He

also walks us through the science of bullying. It’s FASCINATING. For now, know this: “We

secure our sense of belonging through experiences of looking competent in front of the

people whose opinions we care about—earned prestige.” <- We need to help our 10 to 25’s

create this “earned prestige” via high standards and high support as wise mentors.

Now let’s talk about Stress…

STRESS: YOUR BELIEFS?

“Contemporary Western culture has tended to give people problematic beliefs about stress.

Stanford University psychologist Dr. Alia Crum, a key architect of the scientific revolution in the

study of stress, calls it the stress-is-debilitating belief. This is the belief that stress inevitably

harms our performance and health. That belief in turn leads to the conclusion that we should

avoid stress whenever possible.

Often, the stress-is-debilitating belief leads us to a protector mindset. If someone we care about

is experiencing stress and we believe stress is bad, then it makes sense to encourage them to take

action to reduce their stress (e.g., scaling back ambitions). Or we intervene to protect them from

stress (e.g., taking away their responsibilities). …

Other times, the stress-is-debilitating belief can make us enforcers. We say or think something

like, I know that what you’re doing is very stressful, but you need to be gritty and power

through it [or give up] because I can’t do anything to help you. Stress is either a bad thing to

avoid or a bad thing that one must suffer through alone.

Crum’s work has shown that our culture’s stress-is-debilitating belief is both untrue and

unhelpful. It’s untrue because stress is often the natural by-product of us choosing to do

something that is hard that’s important to us. …

The stress-is-debilitating belief is unhelpful because when we believe that stress is debilitating,

and then we notice our stress, we feel even more worried. We may think, What is wrong with me

that I am the kind of person who gets stressed? We stress about being stressed.

What ideas can replace our culture’s stress-is-debilitating belief? Crum has proposed a stresscan-be-enhancing belief. With this belief, stress can serve as a source of energy to fuel improved

performance. With that belief, you can encourage people to lean into their stress—to use it as an

asset. You’re not lowering standards. You’re just helping them see how their body’s stress can act

as a resource to help them meet the higher standard.

When we teach a stress-can-be-enhancing belief, it can convince young people to see some

forms of stress as a positive resource. What’s more, when we emphasize that stress can be

enhancing, and it actually helps them do well, then they remember it. This mentor-mindset

approach to stress—embracing stress, rather than running from it or getting crushed by it—helps

impart a nugget of wisdom that reinforces resilience in the long run.”

STRESS. Viewed properly, it does a Hero good.

Unfortunately, as David tells us, too many of us these days have what Dr. Alia Crum calls a

“stress-is-delibilitating” view of stress. When we hold that perspective, we LITERALLY change

our underlying biology for the worse—our cortisol goes up while our testosterone goes down.

We want to master this wisdom so we can help young people we mentor adopt a “stress-can-beenhancing” mindset. We need to help them see that we can use stress as FUEL for our growth.

The book is PACKED with goodness. But, this is my favorite chapter. We talk about parallel

wisdom in our Notes on Kelly McGonigal’s The Upside of Stress—which is basically a booklength overview of the same research. Check out those Notes for more.

For now, I want to share a couple of blurbs David used in one of the studies he shares that

helped people transform their mindset around stress. He focused on two different messages:

Growth-Mindset Messaging: “When you’re faced with difficult challenges and you keep

trying until you get better, your brain grows new connections and becomes better at taking

on new challenges in the future. … When something does feel really difficult, your brain learns

how to respond more effectively to that challenge. It’s a lot like the way rigorous exercise

makes your muscles really sore at first but, with training, your muscles don’t just get stronger,

they also recover more quickly when you push them to their limit.”

Stress-Can-Be-Enhancing Messaging: “People often mistake their body’s stress response

for a sign that they’re in a situation they can’t handle. It’s easy to do—racing heart, fast

breathing, sweating—these are also ways our bodies respond in emergencies, when we’re in

real trouble. This is a mistake that actually can cause you to perform worse because, if you

think your stress response is a problem, you’re more likely to be worried about it and get

distracted from performing. … You can use your body’s stress response effectively next time

you feel it kicking in while you’re trying to perform or master something difficult. When you

start to feel anxious, try to remind yourself that this is your body’s way of helping you rise and

meet the challenge you’re facing. That should help you to spend less time worrying about the

fact that you feel anxious. Then you can focus on what you’re doing and let your body’s stress

response give you the extra boost you need.”

Of course, we talk about this ALL.THE.TIME. I LOVE the way David frames that.

A MICRO-MOMENT OF LIFE-CHANGING ENCOURAGEMENT

“Dr. Daniel Lapsley is a professor of adolescent psychology at the University of Notre Dame. He

grew up in Pittsburgh, where his father was a coal miner while his mother was a homemaker.

He never thought about college because nobody in his family had ever been. One summer day

in 1965, just before he started seventh grade, Lapsley and his friends were hanging out at a gas

station after playing basketball. Lapsley struck up a conversation with a college-aged guy who

was waiting for his car to get fixed. Soon the topic turned to the Vietnam War. Lapsely was a

reader, and he precociously defended President Johnson’s domino theory of communism in the

region and the United States’ role in the war. The college guy argued the other side in earnest, a

little surprised that Lapsley had done his research, but also encouraging him. He gave no hint of

ridicule, sarcasm, or belittlement. When his car was ready, he turned to Lapsley and said, ‘You

are an extraordinarily bright kid. Have you thought about going to college?’ Then, for reasons

Lapsley still doesn’t understand, he asked if Lapsley had read Dante’s The Divine Comedy and

said how much he would enjoy it—implying that Lapsley would be up for the challenging read.

Lapsely was twelve. He can still remember the exhilarating pride—the earned prestige. ‘I walked

home as if striding mountains. Imagine this stranger urging me to go to college, wondering if

I’ve read Dante.’ This interaction offers a good example of what I mean when I say that earned

prestige is motivating. Eventually Lapsley did indeed go to college, just like the stranger had

recommended. And he never left. He earned his PhD and spent his entire adult life as a college

professor; he now serves as a lead mentor in the university’s program to support first-generation

college students.”

That’s from a chapter in Section III which is all about “Building a Better Future.”

The chapter that precedes it is an incredibly inspiring look at how we create “Inclusive

Excellence” such that disadvantaged groups are best given the opportunity to do truly excellent

work and flourish while making important contributions to their fields and communities. The

main theme of that chapter and how we create inclusive excellence? The essence of the entire

book: the mentor mindset featuring its hallmark of high standards AND high support.

Now… Right after that passage above, Yeager tells us that Lapsley said that “the encounter

with the stranger at the gas station looms larger than any teacher, larger than anything that

happened in any school. The stranger at the gas station planted an idea, raised a possibility

that had not occurred to me. … He made me feel special, talented. … This clear, vivid memory

I have has never shaken. And I credit this encounter, this stranger, with setting me on the path

that was unusual for kids in the steel town of my birth.”

Quotes – David Yeager unless stated otherwise.

“Our society tends to think

that there are only two ways

to interact with young people:

tough or soft, mean or nice,

authoritarian or permissive.

We don’t realize that you can

have a bit of both: you can

have high standards and high

support.”

“Status and respect are to

a young person what food

and sleep are to a baby—core

needs that, when satisfied,

can unlock better motivation

and behavior.”

“The Maori tribe in New

Zealand has a beautiful term

for it: whakamana, which

means ‘to give prestige to,

give authority to, confirm,

enable, authorize, legitimize,

empower, validate.’ (Mana

means ‘power,’ and whaka

means ‘to give.’) Whakamana

is what leaders need to do

to resolve the adolescent

predicament and satisfy young

people’s sensitivity to status

and respect.”

“By giving young people the

thrilling opportunity to earn

prestige—and satisfy their

needs for status and respect—

mentor-mindset leaders offer

them the chance to feel

amazing. Young people soon

learn that if they want to

keep feeling that way (and

avoid feeling humiliated),

they should follow the

mentor-mindset leader. The

enforcer- or protector mindset leads by shaming,

blaming, judging, evaluating,

and controlling young people,

deny the opportunity to earn

prestige. That’s demotivating.”

“A [person] who becomes

conscious of the

responsibility [they] bear

toward a human being who

affectionately waits for

[them], or to an unfinished

work . . . knows the ‘why’

for [their] existence and will

be able to bear almost any

‘how.”

~ Viktor Frankl, Man’s Search for

Meaning (1946)

“Dobson called this solution

a transparency statement: a

simple and clear declaration

of your intentions at the

start of any potentially

threatening interaction.”

“The mentor mindset

transformed the lives of all

young people and especially

those who were marginalized

by their race, ethnicity, or

socioeconomic status.”

“I shall only ask him, and not

teach him, and he shall share

the enquiry with me.”

~ Socrates in Plato’s Meno

“When we mentor for future

growth, it’s far better to give

young people experiences that

show them they are capable

of meeting the high standard

with the appropriate support,

rather than offering them

unfounded assurances of

their abilities—or, worse, hiding

the standards from them

altogether.”

“If young people’s brains

seek social rewards—status,

respect, prestige—and hope to

avoid social failures—shame,

humiliation, rejection—then we

can turn these motivations

into assets, not liabilities, for

healthy development.”